About

Most technologies are made from steel, concrete, chemicals and plastics, which degrade over time and can produce harmful ecological and health side effects. It would thus be useful to build technologies using self-renewing and biocompatible materials, of which the ideal candidates are living systems themselves. Thus, we here present a method that designs completely biological machines from the ground up: computers automatically design new machines in simulation, and the best designs are then built by combining together different biological tissues. This suggests others may use this approach to design a variety of living machines to safely deliver drugs inside the human body, help with environmental remediation, or further broaden our understanding of the diverse forms and functions life may adopt.

Most technologies are made from steel, concrete, chemicals and plastics, which degrade over time and can produce harmful ecological and health side effects. It would thus be useful to build technologies using self-renewing and biocompatible materials, of which the ideal candidates are living systems themselves. Thus, we here present a method that designs completely biological machines from the ground up: computers automatically design new machines in simulation, and the best designs are then built by combining together different biological tissues. This suggests others may use this approach to design a variety of living machines to safely deliver drugs inside the human body, help with environmental remediation, or further broaden our understanding of the diverse forms and functions life may adopt.

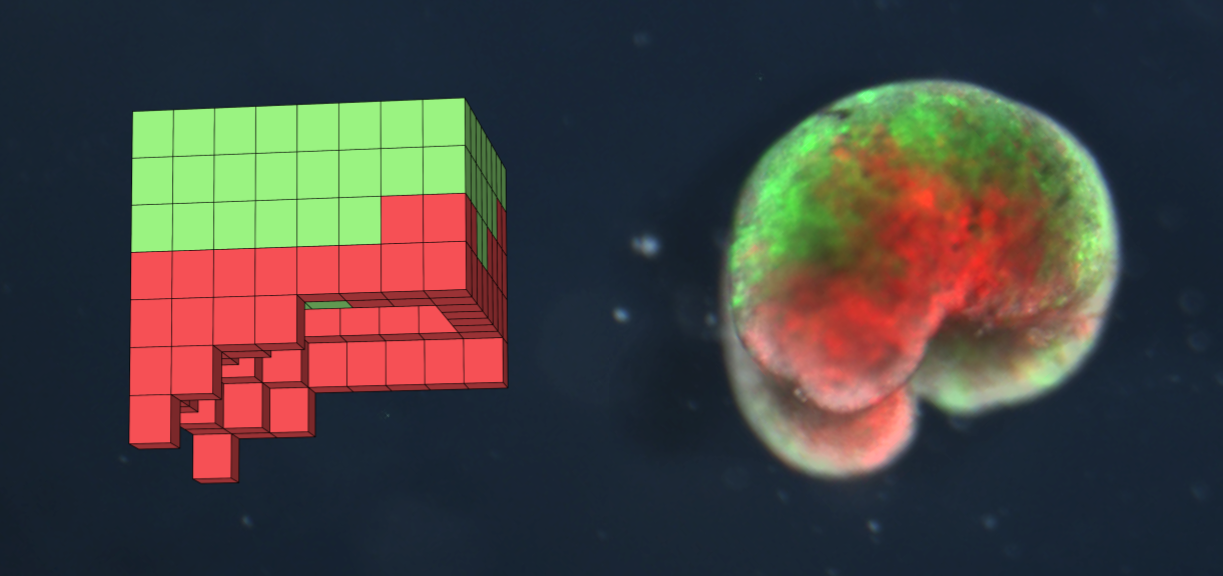

A computer-designed organism (CDO), with the red/green colored design from the above image, walks under the microscope.

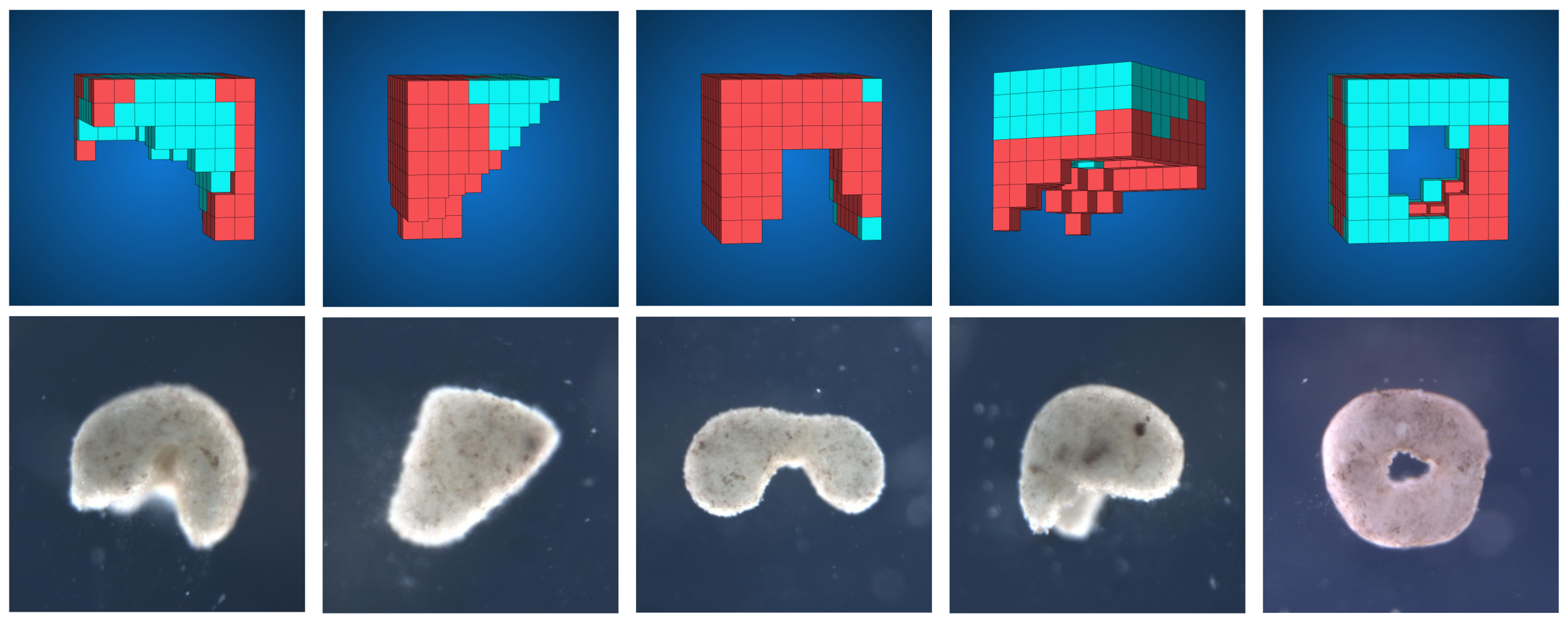

AI methods automatically design diverse candidate lifeforms in simulation (top row) to perform some desired function, and transferable designs are then created using a cell-based construction toolkit to realize living systems (bottom row) with the predicted behaviors.

AI methods automatically design diverse candidate lifeforms in simulation (top row) to perform some desired function, and transferable designs are then created using a cell-based construction toolkit to realize living systems (bottom row) with the predicted behaviors.

How they’re made

Press release

https://www.uvm.edu/uvmnews/news/team-builds-first-living-robots

FAQ

What is the big picture here — is it just about robots made of frog cells?

The big question here is: how do cells cooperate to build complex, functional bodies? How do they know what to build and what signals do they exchange to enable them to build them? This is important not only to understand the evolution of body shapes and the functions of the genome, but for all of biomedicine. Aside from infectious disease, pretty much all other problems of medicine boil down to the control of anatomy. If we could make 3D biological form on demand, we could repair birth defects, reprogram tumors into normal tissue, regenerate after traumatic injury or degenerative disease, and defeat aging (as highly regenerative organisms like planaria do). Stem cell biology and genomic editing do not, on their own, address this issue. It is still unknown what cells are capable of making besides their normal default body pattern, and these synthetic living machines are a convenient sandbox platform in which to make fundamental discoveries. We made these out of normal frog cells, with a normal frog genome. Their bodies look and act completely different from frogs, and can do so despite the fact that these “animals” have no evolutionary history of selection pressure which would have rewarded them for this behavior (they’re skin cells which have been used for millions of years to sit quietly on the surface of a frog and keep out the pathogens). Once we figure out how cells can be motivated to build specific structures, this will not only have a massive impact on regenerative medicine (building body parts and inducing regeneration), but the same principles will lead to better robotics, communication systems, and maybe new (non-neurocentric) AI platforms. The long-term goal here is to figure out how living agents (cells) can be motivated to build specific things, and how to exploit their plasticity and competency to do things that are too hard to micromanage directly (like build an eye, hand, etc.). This is also a part of a critical effort for the future of society and technology: the taming of “unintended consequences” from complex phenomena with surprising emergent outcomes - to understand how to manage swarms and collectives of active agents toward beneficial outcomes. This paper is just the first of a pipeline of studies in progress, extending the work toward applications in biomedicine, robotics, and synthetic morphology.

What kinds of biological tissues were used to build computer-designed organisms?

Frog skin (green in the above image) and heart muscle (red). Both were derived from cells harvested from blastula stage Xenopus laevis embryos. These tissues naturally develop cilia (waving hairs which enable swimming), but the cilia were removed in the green/red colored organism to producing a walking (instead of swimming) organism.

How big/small are the organisms?

The red/green colored organism pictured above is about 0.7 millimeters. It was carved from a 10000 cell sphere, and its final geometry contains about 5000 cells.

What have they been used for?

So far we have built computer-designed organisms that walk, swim, push/carry an object, and work together in groups.

Why do these count as organisms?

They “live” for about seven days, after which they stop functioning (a positive feature in terms of safety for synthetic biology constructs). Although, like vast numbers of organisms on Earth, they do not contain a brain, they exhibit functional behavior, are able to heal themselves if damaged, and work collectively. They can’t reproduce, but there are naturally occurring organisms that can’t either (e.g. mules). Synthetic living machines push biologists to develop deeper and more rigorous definitions of what an “organism” is. The question of what exactly makes for an organism (given the many colonial, syncitial, microbiome-bearing organisms are found in the natural world) is not an easy one; but these show the kind of coordinated structure and function that are immediately recognizable as belonging to a coherent organism.

Are these organisms aquatic?

The organisms live in standard freshwater and can survive in temperatures ranging from 40 degrees to 80 degrees fahrenheit.

Do the organisms eat?

The organisms come pre-loaded with their own food source (lipid and protein deposits) allowing them to live for a little over a week. However if grown in a nutrient rich cell-culture media, their lifespan can be increased to weeks or months.

How do computers design organisms?

Computers model the dynamics of the biological building blocks (skin and heart muscle) and use them like LEGO bricks to build different organism anatomies. The behavior of each designed anatomy is simulated in a physics-based virtual environment and assigned a performance score (e.g. distance traveled). An evolutionary algorithm starts with a population of randomly-assembled designs, then iteratively deletes the worst ones and replaces them by randomly-mutated copies of the better ones. It is the survival of the fittest, inside the computer. The fittest designs in virtual reality are then selected to be built out of real biological tissues.

How do you compare the similarity of the computer’s design with the actual organism that is built?

The behavior of organisms was traced and compared with the virtual design. To determine whether the organisms’ movement was a result of chance or due to the design’s evolved geometry and tissue placement, geometry and tissue distribution was altered by rotating the design 180° about its transverse plane (flipping it over onto its “back”). The shape and tissue placement of the built organism was compared using computer vision.

Why make new organisms?

Nature has only explored a vanishingly small part of the space of organisms that could be assembled from biological cells. What else is out there? We need to understand (a) what kinds of structures cells are able to cooperate towards building, (b) how they decide what to make, when liberated from their normal context (how much plasticity is there), (c) what is possible without editing the genome, and (d) how complex outcomes can be manipulated rationally.

What fundamental questions does such work answer?

This project seeks to determine the degree of emergent cooperation that cells can exhibit without genomic editing when liberated from the normal constraints of an embryo. In other words, what other functionalities exist in the physiological software encoded by a standard frog genome? Information about how cells make decisions during the process of assembling a new body sheds light on the origin of multicellularity, the computational capabilities of single cells, the exploitation of physical forces by evolution, the origin and specification of the default bodyplan normally built by embryonic cells, and the capacity for bioengineering new living machines with useful functions.

Why are computer-designed organisms called “reconfigurable organisms” in the technical paper?

Frog cells were pieced together to form a new configuration, which is different from a frog. The cells which were configured by natural selection to become frogs were reconfigured by AI to create new forms and functions. The aggregated cells of the resulting organism can also be disassociated and reconfigured to form a new organism.

Why are computer-designed organisms nicknamed “Xenobots”?

The cells used to build the first CDOs came from early embryos of the African clawed frog. The taxonomic name for this frog is Xenopus laevis. Xeno also means “other” or “strange” which highlights the fact that these cells do things different from their genomic default bodyplan.

Couldn’t these constructs start evolving beyond our control?

There is no evolution here: these CDOs have no reproductive organs. They simply degrade and become non-functional after about seven days. However, living organisms (those made by human-guided mating, bacteria and viruses generated by human travel and impact on the foodchain, etc.) do evolve beyond our control all the time; the best way to deal with this fact going forward is to understand it and learn to guide it.

What advantages and disadvantages do CDOs have over microrobots?

Microrobots are made from metal, ceramics and plastics, so they are stronger and can thus, in theory, survive longer than CDOs. But, small amounts of metal can be very harmful for internal organs; CDOs are completely biocompatible and biodegradable.

If an AI did indeed design these organisms, couldn’t an evil (or ignorant) AI design harmful (or unintentionally harmful) organisms?

An AI intent on causing harm seems unlikely, but designing organisms with unintentional side effects is a possible outcome for this technology. We thus believe that all computer-designed technologies — including organisms — require human verification before being created physically, let alone deployed to perform (hopefully) useful work. Further, regulation of such technology is an important next step in the policy space. Regardless, the potential of harm in these kinds of creations is infinitely smaller than current efforts in the virology, bacteriology, and genome editing spaces.

Couldn’t someone program the AI to design weaponized CDOs?

In theory, yes. At the moment though it is difficult to see how an AI could create harmful organisms any easier than a talented biologist with bad intentions could. Despite this, we believe that, as this technology matures, regulation of its use and misuse should be a high priority. Again though, the possibility of misuse is much, much smaller than what is being done with self-reproducing agents like bacteria, viruses, and gene drives.